The Upper Levels

The Ferreira Gomez Theater was one of the most special theaters in Rio. It was not the prettiest, nor the largest, nor the one presenting the best plays in the city, but its allure laid in its original performances in untranslated French and English, attracting a selected public of foreign dignitaries, diplomats, and assorted snobs. Actors and directors from the world over came to present their productions at the Ferreira Gomez Theater, knowing that they could not only trust the crew to produce a play without distorting their words in nonsense translations but expect to be understood by the attending public as well. It was in this environment of cosmopolitan splendor that Antenor Assis started his career as a performer, first as a wordless extra, then as a stand-in, and finally as a supporting actor in the theater’s longest-running shows.

Antenor Assis was not English nor French, but he had the luck of being born into a traditional oligarchic family of coffee traders, who still educated their children in the old ways of hiring private tutors and drilling them with endless classes on arithmetics, Latin, and foreign languages. Consequently, his domain of the French language was superb, and with English he did well enough to recite a limited number of lines when needed. His parents were not at all surprised when he announced his interest in abandoning the family's property to try his luck as a thespian in the nation’s capital, after all in these traditional clans one of the children always ends up as a failed artist, opium addict painter or poet with homosexual tendencies, and since Antenor was the youngest of four brothers, he would play no important part in the conduction of family’s business anyway.

It was the summer of 1938 when the theater’s managers announced they would receive a cast ensemble from Moscow for a limited season of Gorky’s The Lower Depths. This announcement put the whole theater in turmoil, as receiving actors from the secluded Soviet Union was akin to receiving actors from Mars. On the day of their arrival, the whole team went to wait for the ensemble in Rio’s port, and Antenor Assis joined them. It was one of those stuffy and torrid mornings, common to the tropical climate of Southeastern Brazil, and Antenor wondered if the heat would not make the Russians go into an apoplectic fit. He watched as the ship carrying the cast docked at the harbour and soon its cargo of slavic men and women disembarked. The theater’s manager - an aged intellectual rumored to be a pederast, and with a physiognomy that gave meat to the rumors - was the first to extend his greetings to the Russians, who, for Antenor’s surprise, were not the beige, muscular industrial workers he expected, but elegant and graceful aesthetes, almost all with bright blue eyes and brownish-blonde hair. They introduced each other and Antenor noticed the Eastern inflections in his guest’s French, which only made them more charming in his eyes. The two ensembles finished the day with a visit to the theater and a three-course meal at the London Hotel for an early night before the season's kick off.

The rehearsals started almost immediately. While the Brazilian side of the ensemble - limited to supporting roles and technical matters - needed time to acclimatize itself to the text, the Russians already had their parts fully memorized from previous seasons at various North American harbors. Thus, the rehearsal period went by in an easy-going manner for the Russians and an anxious, almost apologetic one for the Brazilians. However, the former held no ill will towards their hosts, and took benefit of their careless days to strike short friendships with their South American partners. Antenor Assis became friendly with one of the main actors, a Russian by the name of Stepan Vasillovitch, affectionately called Stepik, who insisted on using every opportunity to engage in conversation with Assis about his life and times. He was a good one head taller than Antenor, with the broad shoulders of a swimmer, and facial traits that reminded one of the defunct Tsar Nicholas. Through bouts of conversation both inside the theater and in a nearby bar (lubricated by several watered-down Brazilian beers, an unexpected success among the Russians), Stepik revealed many details of his own life, describing his youth in Harbin as a White emigrée, his return to Moscow through the Trans-Siberian railway, anxiously brooding in the train as the countdown to arrival at the epicenter of Stalin’s kingdom retreated with each passing province, his days as a “non-person” and his eventual redemption as an actor in the Rabochaya Association of Dramatic Arts. But the most surprising confession came inside theater grounds when after passing lines back and forth, Stepan Vasillovitch confessed to Antenor Assis that he was actually the nephew of a petty noble who was a former governor of Yaroslav, showing the tattoo of a dragon he had marked on his forearm.

Antenor Assis was very surprised by this news, and it would be a lie to say it didn’t affect how he treated Stepik from then on. Although by all means Antenor represented a de-facto aristocracy in his society, he had never actually interacted with nobility before, as the seat of his family’s coffee empire was too isolated to allow him to regularly meet decadent barons and former nobles of the fallen Brazilian Empire. In fact, for most of his childhood, he was raised either by British housekeepers of staunchly bourgeois backgrounds or freed blacks, so he ignored how he should behave in the company of actual lords and peers. What puzzled him the most, however, was how the descendant of a noble house could represent the Soviet government in what was a formally state-funded cultural tour. Having developed a level of intimacy with Stepik, Antenor Assis inquired Why he was allowed to represent a proletarian society, he who was not and could never be a proletarian himself. Stepik laughed, first thanked his friend for not imprinting any judgment of value to his revelation and then explained the following: After the end of the revolutionary period and the civil war, when Russia was more or less stabilized, the regime decided that the best way to advance the legitimacy of the newly-founded Soviet republic would be to promote Russian art - including suspect pre-revolutionary art like Pushkin and Turgenev - through government-sponsored productions. Thus, the state built new theaters and drama schools, universities, and reading centers, forming actors ensembles across the most remote provinces of the Union, even among the Tatars and Mongols of the distant Turkestan. There was just one problem. When the first plays were finally staged, the intelligentsia found out that workers could not convincingly act as nobles. And what was worse, they could not act as the lumpen either. Faced with disastrous productions of appalling quality, the bureaucracy at the Ministry of Culture started getting desperate, afraid of being accused of sabotage and ending up shot or convicted to 10 years of forced labor. They realized what everyone knew but could not admit: only a noble knows how the play the poor. The bureaucrats proceeded to turn over every labor camp and every Gulag to find imprisoned nobles with a dramatic background and force them into a stage. They found directors toiling in the Moscow-Volga canal and stage producers freezing in Karaganda. A costume designer had just been sentenced to death and was waiting in his dungeon to be shot when, in true Russian fashion, he received not his expected mercy bullet but an official pardon and an invitation to join the Minsk National Theater. One day, in a certain production, the crew noticed that nobody could imitate the ringing of a church bell, and it was impossible to find a legitimate bell ringer in the Moscow of the Great Stalin. Only after a desperate search an old monk who used to be a bell-ringer in a monastery was discovered in a concentration camp near the Arctic. All the man’s alleged crimes were instantly erased and he was sent to Moscow to spend the rest of his life ringing bells at the theater. I myself thought I would be arrested as soon as I set foot in Moscow, continued Stepik, but what greeted me was a proposal to join this cast due to my French proficiency, and I accepted it without reservations. Now I live for the stage, under the protection of Molotov and Yezhov, behind the gaze of the great Pantocrator eye himself. “So you are all nobles” Antenor asked “Yes” he confirmed, “and mind you I am only a petty noble. My colleague Vanya would be a Count today if the old regime was still around, and Maria Affimova is herself a bonafide princess”.

Until now Antenor Assis had not paid attention to this so-called Maria Affimova, but after this revelation his eyes wandered away from his friend in search of her, stopping only when they found the princess, and Antenor Assis was struck by her great beauty, a beauty until then occult but now beaming out of her figure, covering her in a veil of natural dignity even through the rags of her costume as Vasilisa Karpovna, the petty landlord’s wife. She was a middle-aged woman, with two droopy brown eyes like the ones of a beagle, which should tarnish her looks but only served to confer her an even more attractive glow. Antenor Assis was mesmerized by the realization of Maria Affimova’s beauty and was immediately smitten. It took him a true effort to stop staring and bring his attention back to his friend.

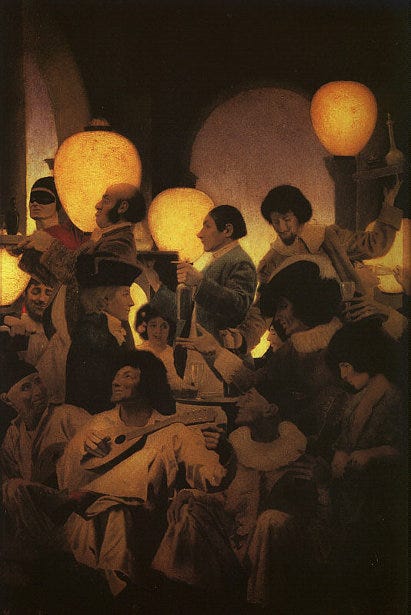

The rehearsal ended and the opening days arrived, with the play mixing Russian and Brazilian actors being critically acclaimed. The reviewers were charmed by the soviet visitors, announcing the play as the beginning of an era of straighter bonds between continents, with local dignitaries declaring that they would soon send a cast ensemble to further friendship ties with Moscow. All through the two weeks of production Antenor Assis awaited expectantly for Maria Affimova’s appearance on the stage, and he thanked his luck that they did not share any scene, so he could admire her from the aisles without interruptions. Every time the cast was together he tried to be near her, but these opportunities became rarer and rarer as the Russians were taken to increasingly more convoluted official visits, media appearances and tours on natural sites of Rio de Janeiro. For this reason, Antenor Assis was looking forward to their joint dinner at closing night, where he would do his best to sit by her side and engage in conversation. When the day arrived, the crew hurried up to the restaurant after the final curtain call for much wine and beer, and Antenor followed. There he searched for Maria Affimova but could not find her anywhere. Disappointed, he discovered that she had decided not to follow them to the restaurant and who sat by his side was not the princess but his friend Stepan Vasillovitch. Antenor tried to keep his hopes up, expectant that soon she would regret her decision to not join her colleagues, crossing the halls of the restaurant at any moment now and pulling a chair to sit with them, one that would be conveniently pulled right by the side of Antenor Assis. But as the night went by it was obvious that this fantasy would not take place, and he tried to distract himself with conversation. At the table the discussion had turned to Russian literature, and the question in debate was if it could serve as a mirror for all society or only for Russian life. Most of the table was of the opinion that yes, any person, no matter where, could see themselves reflected in the words of the Russian writers, and that was Russian literature’s greatest merit, this sense of universality, but Stepan Vasillovitch disagreed, and more than that, he tried to make the case that literature could not even sufficiently represent a single human life and that the writing world was still waiting for a total work of art. Antenor asked Stepik to explain himself, and so he did, getting visibly drunker by the minute. He pulled Antenor by his collar and approached the Brazilian’s face towards his mouth, explaining: “Imagine Dostoievsky. You know that Dostoievsky lived a full life, and he did successfully transfer his own experiences of religious apprehension and existential crisis to the paper. This would appear to deny my argument about the limitations of Russian literature in particular and all of literature in general. However consider this: We know for a fact that Dostoievsky was a man, and as a man he certainly shat during the course of his life. Yet we never see Aliosha shitting, nor Prince Mishkin nor Raskolnikov. Similarly, we know that Tolstoi shat, and so did Andrei Bely, and so did Lermontov, and even the great Pushkin certainly took a shit every once in a while, yet none of their characters ever shit. In fact, almost no work of literature has a description of someone taking a shit, even though shitting is an universal human experience that is shared by everyone. if writers have failed to successfully represent this most basic character of humanity, what other essential experiences have they also missed? Something deeper and more profound than shitting, of course, but what it is I ignore, as we have been unable to venture beyond even the surface of escatological knowledge.” Throughout this monologue Antenor started to feel increasingly more nauseous, and he could not tell if it was the drink, the atrocious conversation with Stepik or the overwhelming smoke coming from thousands of lit cigars in the hall. He excused himself and went to the bathroom, but instead changed his course halfway and walked out of the restaurant.

Outside, twilight had not yet set. Antenor Assis walked down the street, passing by the classicist-style buildings to his left and right (which today most were torn down and replaced by graceless monstrosities) reaching the beach’s promenade. He took a right and started walking towards Cantagalo hill, flanked by the sea and the sand, with the downward movement of the sun in front of him. Antenor watched the sky changing colors as the sun fell behind the line of the horizon. When he was almost at the corner between Ipanema and Copacabana, Antenor Assis saw that in his opposite direction came walking Maria Affimova, for the first time not wearing the rags of the landlord’s wife, but her regular clothes, and her beauty seemed many times enhanced by the simple dress she wore and the last glow of the sunset upon the sky. Antenor Assis gazed at her and decided that this was the time to say something, but nothing came out of his mouth. They both continued walking towards one another, and by now their eyes had locked and there could be no reasonable doubt if either were to argue that neither recognized each other. Their path continued converging, and Antenor could not explain why he wouldn’t stop, why he wouldn’t hold Maria’s hand and say one or two charming words to her, perhaps invite her to dine with him during this last day when they could still enjoy one another’s company. He continued walking, and he felt like he was walking towards the core of a glowing star, a star that would devour his body and obliterate any sign of his existence, returning his atoms to the cosmic void that once had gestated him. The couple continued to share a silent stare, and Antenor noted that Maria Affimova’s eyes changed as he approached, first pleading and then demanding, but still, nothing was said. Their paths crossed and Antenor Assis opened his mouth and closed it again, looking forcibly onwards and trying to ignore the body of mass passing by his side. He did not turn his back to check if Maria had stopped to look at him. He would’ve made a great Orpheus.

Antenor Assis continued to walk until the night fell, and he still walked even longer after that. Eventually, he took a tram back home and quickly fell asleep. The next day the Brazilian actors followed the Russians to their ship and embraced as the Slavs departed to their next stop in Punta del Este. Antenor Assis did not attend the farewells, and the planned visit to Moscow never became more than mere promises.